The medical model of disability is a way of thinking about disability that focuses on the individual’s physical or mental condition. It views disability as a problem or deficit that exists within the person and assumes that the best way to address it is through medical treatment, rehabilitation, or cure. This approach sees disability largely as a clinical matter and prioritises medical intervention over social changes or environmental adjustments.

Under this model, the disabled person is typically described in terms of their diagnosis or impairment. The emphasis rests on what the person cannot do because of their condition. The idea is that if the condition can be treated or managed medically, the person’s life will be improved and their limitations reduced.

Origins of the Medical Model

The medical model developed during a time when medical science was becoming more advanced and society placed great trust in doctors, surgeons, and scientists. For many conditions, medical treatment made a dramatic difference in quality of life. This reinforced the belief that disability could be resolved primarily through healthcare.

Historically, this model grew out of a clinical viewpoint in which illness, injury, and impairment were identified, labelled, and treated as individual problems. In this approach, the role of health professionals is central, and their expertise is considered the main route to reducing or removing disability.

Characteristics of the Model

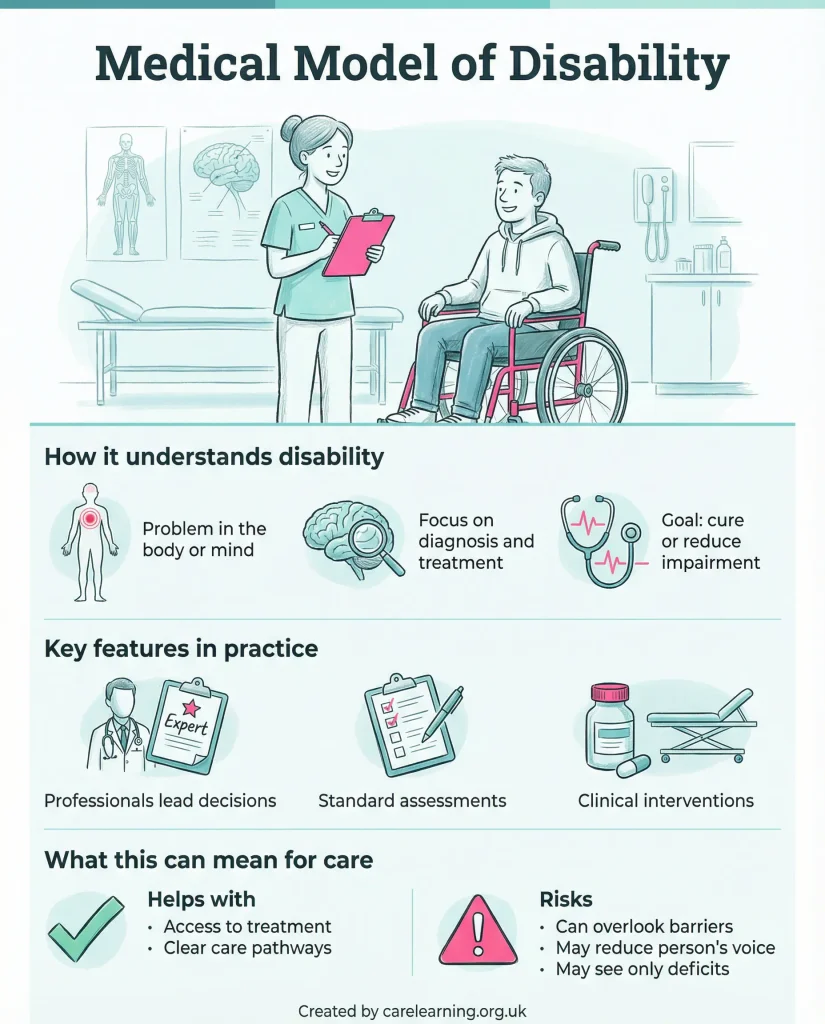

Key features of the medical model include:

- Disability is defined by impairment or medical condition.

- The focus is on diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment.

- Experts such as doctors and therapists are seen as the main agents of change.

- The cause of the problem is located in the individual’s body or mind.

- Solutions are sought through medical intervention or therapy.

This perspective frames disability in terms of physical functioning and mental capacity. The surroundings or societal attitudes are considered secondary, with the main aim being to restore the person as much as possible to what is seen as normal functioning.

How Disability Is Viewed

Within the medical model, disability is often seen as a personal tragedy. A person who cannot walk, for example, is regarded as disadvantaged because of their inability to move in a way that most people do. The approach then asks: what can medicine or rehabilitation do to help them walk, or replace that function? This reflects a focus on fixing or compensating for an impairment rather than removing barriers that stop the person from taking part fully in life.

Under the medical model, society’s role is limited. It suggests that once medical help is provided, the individual’s participation and quality of life will improve naturally. This often overlooks the broader context, such as inaccessible buildings or workplace prejudices that can continue to restrict opportunities, regardless of any medical gains.

Impact on Policy and Practice

The medical model has influenced how services are organised. It has led to:

- Programmes that focus on physical rehabilitation as the main resource.

- Assessments that prioritise the severity of impairment when deciding eligibility for support.

- Educational settings that concentrate on therapy and treatment over inclusion in mainstream activities.

- Funding going primarily towards medical and healthcare solutions rather than community or environmental changes.

For example, a child with hearing loss might be offered hearing aids, speech therapy, or surgery, but little attention might be given to adapting classrooms with sound amplification systems or training teachers to communicate effectively.

Criticisms of the Medical Model

Many people have criticised the medical model for being narrow in its view of disability. One common criticism is that it puts too much focus on the impairment and not enough on social factors that create barriers. Another is that it can lead disabled people to be seen as dependent on health professionals rather than active members of society.

Critics argue that this model can lead to:

- Labelling and stereotyping based on diagnosis.

- Reduced expectations for what disabled people can achieve.

- Services designed around medical priorities rather than social inclusion.

- Policies that ignore discrimination or lack of accessibility.

This can have a real emotional impact. If disability is always presented as a personal deficit in need of fixing, it can contribute to feelings of inadequacy and exclusion.

Examples of the Medical Model of Disability

In everyday life, the medical model is often visible in:

- Hospital-based rehabilitation for stroke survivors, with little focus on reintegration into work or community life.

- Eligibility criteria for benefits that rely heavily on medical evidence, such as reports from doctors about functional limitations.

- Plans for disabled students that set academic goals based on physical or mental capabilities rather than changing the learning environment to match their needs.

These examples show that the model directs resources and planning towards individual medical improvement rather than changing structures, attitudes, or services.

What are the Differences from Other Models?

The social model of disability is often discussed alongside the medical model as an alternative. The social model focuses on the idea that disability is created by barriers in society, such as inaccessible buildings, prejudice, or inflexible processes. In that view, the impairment may cause some difficulty, but it is the environment and other people’s behaviour that turn impairment into disability.

By contrast, the medical model pays little attention to these external factors, focusing instead on treatment. Both models aim to improve lives, but they do so in very different ways. The medical model concentrates on the body and mind; the social model concentrates on the world around the person.

Strengths and Limitations

Supporters point out that the medical model has improved many lives by restoring function, relieving pain, and slowing the progress of certain conditions. It has contributed to advances in surgery, medication, and rehabilitation techniques.

However, its limitations are widely recognised. These include:

- Narrow scope that misses social and environmental factors.

- Over-reliance on medical language and expertise, which can exclude the voice of the disabled person.

- A tendency to assume that the person’s quality of life depends on medical success.

In practice, some people benefit from medical interventions but still face daily restrictions because external barriers remain untouched.

The Role of Health Professionals

In the medical model, doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and other healthcare staff are seen as the main agents helping to reduce disability. They work within a clinical framework to assess, diagnose, and treat impairments.

Their role includes:

- Providing medical care to reduce symptoms.

- Offering therapy to increase physical or mental function.

- Advising on medical aids or equipment.

- Monitoring progress and adjusting treatments.

This places great responsibility on health professionals and can diminish the role that family, friends, employers, and communities play in supporting participation.

Public and Cultural Influence

The medical model has shaped the way many people in society think about disability. It has contributed to an image of disabled people as patients in need of care. Media coverage often reflects this viewpoint by focusing on medical stories about cures and recovery.

Some people find reassurance in the idea that disability is a matter for doctors, but it can lead to the false belief that once treatment has been given, the problem is fully resolved. This can make it easy to ignore structural inequality and access issues.

Move Towards Combining Approaches

In more recent years, service providers have often combined elements of the medical model with other approaches. For example, medical treatment might be offered alongside changes to buildings, flexible work arrangements, or awareness training.

This reflects an understanding that medical care can improve function but does not automatically remove all obstacles to participation. In this way, balanced strategies can acknowledge the role of healthcare while working to reduce environmental and social barriers at the same time.

Final Thoughts

The medical model of disability is one of the oldest and most widespread ways of thinking about disability. It places the cause of the problem inside the person and directs solutions towards treatment, rehabilitation, or cure. Many people have benefited from medical advances that restore health or improve function, and this model has played a role in such progress.

At the same time, it has been criticised for overlooking the impact of the environment and societal attitudes. When disability is seen only in medical terms, barriers in workplaces, public spaces, and social participation can remain unaddressed. This means that even after successful treatment, disabled people might still face exclusion.

For a full picture, many experts and organisations now use approaches that combine the medical model with models that address social and environmental change. Doing so can improve health while giving greater attention to the wider factors that shape disabled people’s lives.

Applying Knowledge and Examples

- Keep it person-led: Focus on what matters day-to-day (comfort, access, routines, goals) rather than only on “fixing” impairment.

- Use respectful language: Ask how the person describes their disability and mirror their preferred terms in conversations and records.

- Remove barriers: Make reasonable adjustments in communication and environment (time, noise, format) so the person can participate fully.

- Shared decisions: Explain options clearly, check understanding, and record choices in a way that reflects the person’s views.

Responsibilities and Legislation

- Equality Act 2010: Avoid framing disability as solely “deficit”; focus on removing barriers and providing reasonable adjustments.

- Human rights and dignity: Support autonomy, privacy, and respectful treatment in line with rights-based practice and organisational standards.

- Person-centred planning: Agree goals based on what matters to the person, not only clinical perspectives, and record preferences consistently.

- Consent and capacity: Do not assume incapacity; support decision-making and follow Mental Capacity Act processes where required.

- Advocacy and safeguarding: Use local advocacy routes and safeguarding procedures if barriers prevent the person’s voice being heard or risks are present.

Further Learning and References

- Introduction to the Social and Medical Models of Disability

Accessible overview contrasting models and explaining how medical-model thinking focuses on impairment and “fixing”. - 1.2.1 The social and medical models of disability

Explains the medical model alongside the social model, useful for understanding implications for care and inclusion. - Invisible Disabilities in Education and Employment

Summarises the social model and discusses criticism of medical-model assumptions that can shape policy and practice.

Subscribe to Newsletter

Get the latest news and updates from Care Learning and be first to know about our free courses when they launch.